Forgotten Local Histories: An Englishmen in (Bonaparte’s) Paris – Tales from Napoleon’s capital from a Warwickshire aristocrat

Nineteenth Century Paris

On December 23, 1802, Warwickshire aristocrat Bertie Greatheed stepped into the wintry Paris air.He, like many wealthy Britons, had chosen to visit the French capital now that Britain and France were no longer at war after the peace of Amiens.Paris in the early-19th century was a sprawling city with a 547,000 strong population, which made it the second largest city in the world after London.There were fashionable districts near the Louvre, however many Parisian buildings were old and dilapidated. The streets were narrow, dark, and winding, and congested with traffic (horses, carts and carriages). Perhaps worst of all, there was only 15 miles of sewers (compared to 1,300 miles now).

Modernising the City of Light

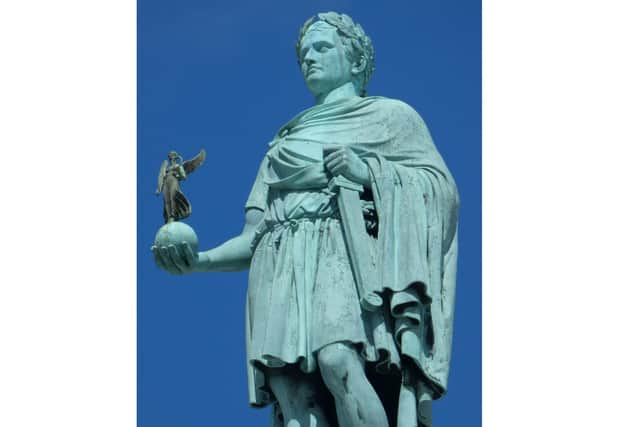

Napoleon Bonaparte, the First Consul of France and head of the Consulate (the French government) had started to make adjustments to the Parisian cityscape. However, the main effort to modernise Paris into the city we broadly know today did not commence until the reign of Napoleon III (more on him in a few weeks’ time).Nevertheless, the future city of light was a major draw for British tourists. Many relished the opportunity to return to Paris after nearly a decade of conflict with France during the French Revolutionary wars.

Bertie Greatheed

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMuch like modern tourists to Paris, the main attractions for nineteenth century visitors included the Louvre, the Pantheon, and the Hotel of the Invalides.However, Bertie Greatheed was not a simple sightseer. His continental education in Gottingen - which, at the time, was considered the best university in the world, even above Oxford - had resulted in him developing a taste for travel, literature and art over the traditional country pursuits of hunting and shooting.Therefore, in the words of JPT Bury and JC Barry (1953), it is unsurprising that ‘the Greatheeds’ journey [to Paris] was primarily a pilgrimage to the mecca of art’.

The Louvre

The Greatheeds’ son, Bertie Jr, was a talented artist. All the family were eager for him to see and study the great masterpieces which, as a result of French military conquests, could be seen in the Louvre.It was an opportunity fully maximised by Bertie Jr, and Greatheed Sr later reported that visits to the gallery ‘took up a part of every morning’ of the trip.The Greatheeds were impressed by what they saw in the Louvre: ‘such an assemblage of the treasures of art never existed before…the eye was so taken up with everything, that it could scarcely rest on anything’.To top it all off, the facilities available for studying and writing about the collection were deemed to be ‘perfect’.

The darker side of Paris

Less perfect was Bertie senior’s experience of Parisian punctuality. Greatheed was especially irritated one evening when a guest failed to turn up for dinner and he ‘again complained that nothing went smoothly in Paris’.Even more concerning for the Greatheeds was the military presence in the French capital. Nancy Greatheed was ‘afraid of every word she said being reported’, and Bertie Sr. thought it unsafe to write down too much criticism of the French government in fear that his diaries would incriminate him if they were confiscated by the authorities.An incident that underlined these fears was when Bertie Sr. saw the police try to arrest a man but eventually leave him alone once they discovered he was the wrong person. ‘Curious work to execute first and investigate afterwards’, he reflected.

Betraying the French Revolution

More widely, many Britons, Bertie Sr included, thought that the militaristic, police-like state of the Consulate had undermined the values of the French Revolution (i.e. liberty, equality and fraternity) that it claimed to have ended.As Bertie Sr said: ‘Perhaps the bulk of people are better off [under the Consulate] but I see no exultation…no pride…Bonaparte has given them quiet and they wanted quiet. He has an army and therefore they obey him’.Not that the French people really cared what these foreign visitors thought. Most were pleased with the Consulate’s reforms and were grateful that the country was at peace for the first time in ten years.The major draw for Britons to Paris during the truce that we have not yet discussed was their desire to either see or have an audience with the First Consul himself. Bertie Greatheed was not to be deprived of this experience, as we shall see next week.

Author’s Note:

Thanks to the staff at the Warwickshire County Records Office for their assistance sourcing materials for this article.

Next Week’s Article:

When Bertie met Boney: An Audience with Napoleon