Forgotten Local Histories: King Edward II’s imprisonment at Kenilworth Castle

A harrowing picture is painted in Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II of the eponymous king’s imprisonment following the usurpation by Lord Mortimer and Queen Isabella.

Indeed, in Act 5 Scene III, Edward laments his condition: starved of food in a foul dungeon, begging his gaolers for water. Cruelly, all they provide to drink is rainwater from a puddle and, Edward laments, a ‘daily diet [of] sobs that almost rent the closet of my heart’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is the portrait of a pitiful figure, a king fallen from grace who is no longer afforded any fanfare upon his arrival at royal fortresses, as we see when one of Edward’s gaolers orders those escorting the prisoner to ‘put out the torches: we’ll enter into darkness to Killingworth [i.e. Kenilworth]’.

The drama in Marlowe’s account of Edward’s imprisonment is not altogether surprising given the playwright’s occupation or the purpose of the play (to entertain). Nevertheless, authors and historians have, over the centuries, persistently seen the poetry and drama in Edward II’s fate.

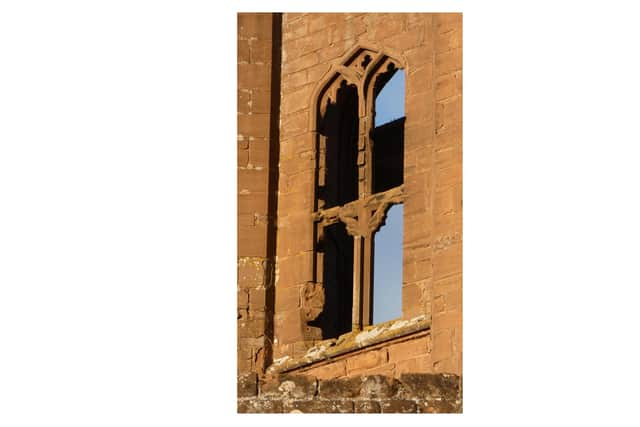

Writing on the history of Kenilworth Castle in 1949, Arthur Mee reflects on how Edward ‘would gaze in dismay on these stout walls [and, here, would] spend some of the unhappiest of his last unhappy days, soon to be ended at Berkeley Castle’.

Mee goes further in describing the tragedy of Edward’s fate: ‘the country round Kenilworth would be calm and lovely, then as now. He would find much to reflect on as he gazed from his window before his captors came to take him away to more indignities. The rooks wheel mournfully above where we stand; it is as though they are mindful of the doom of the mighty dead’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMee’s description of events are romanticised and seemingly designed to invoke sympathy for the deposed king. However, this is not to say that his description is not apt. Indeed, it invokes well the tragic circumstances that Edward found himself in.

In the words of scholar Seymour Phillips, writing in 2012, Edward was a ‘man who had so recently been in a position of power with all the trappings of royalty and was now separated from family, friends and dignity’. Therefore, it would not be surprising if he were experiencing some form of depression.

In the purest historical sense, we do not know what Edward ruminated on during his time as a prisoner at Kenilworth Castle. In fact, we do not know much at all about his time in captivity.

However, we do know that Edward arrived at Kenilworth in early-December 1326, having first travelled via Monmouth and Ledbury, and he stayed until early-April 1327.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdContrary to popular belief, Edward was seemingly well-treated. At one stage, he even received a gift of two tuns of Rhenish wine, sent to him by his son (who was to become the new King at the expense of his father).

Nevertheless, gifts of this nature were probably of little consolation to a man, cut off from his family and friends, whose circumstances had changed so dramatically.

The facts surrounding the final months of Edward’s life, when he was moved from Kenilworth to Berkeley Castle, are equally as obscure.

The traditional narrative states that Roger Mortimer authorised Edward’s move to Berkeley so that the former could have the latter killed. However, there is also a theory suggesting that the decision to move Edward was based on security concerns.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis interpretation suggests that Edward’s captors feared a plot to free him from Kenilworth Castle.

Therefore, they petitioned to have the prisoner transferred to a safer location - Berkeley Castle - where Edward eventually arrived on 5 April 1327.

The move seemed to do little to deter the plotters, however, as they apparently tried to free Edward from Berkeley, even getting so far as to make contact with him, if not necessarily free him.

Edward would spend the rest of his days at Berkeley, possibly excepting a brief tour around several other castles in an attempt to foil the plotters’ other plans to free him. He died at the castle on 21 September 1327.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne cannot end a history of Edward II without discussing the manner of his death.

It is possible that Edward died of natural causes, or that he was ‘subtly’ murdered in a way designed to suggest natural death (e.g. strangulation).

However, readers will be more familiar with the suggestion that he was killed with a ‘red hot poker’.

There is ultimately no evidence to suggest that Edward died in this manner, so why has it become so infamous?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne proposal is that the story has turned into ‘fact’ simply because it has been so frequently repeated (an example of the ‘illusory truth’ principle).

Another explanation is that the story emerged as a propaganda tool. Contemporaries could feasibly have used the homosexual connotations of the story as a rhetorical weapon to undermine Edward II and, therefore, lend further justification to the act of deposing him.

This may seem a deeply unpalatable political weapon to us today, but it was not an uncommon tool in the medieval world.

There also exists a school of thought that Edward II did not die at Berkeley Castle. Rather, he escaped to the continent and possibly lived until as late as 1341.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis, however, remains a controversial view; and like many historical controversies, we simply do not have the evidence to say for certain exactly what happened.

Author’s Note: With thanks to Jan Cooper, Chair of the Kenilworth History and Archaeology Society, for her insightful comments and reading suggestions for this subject. Any and all errors are my own.

Next Week’s Article: Did William Shakespeare meet Queen Elizabeth? The story of the Princely Pleasures of 1575