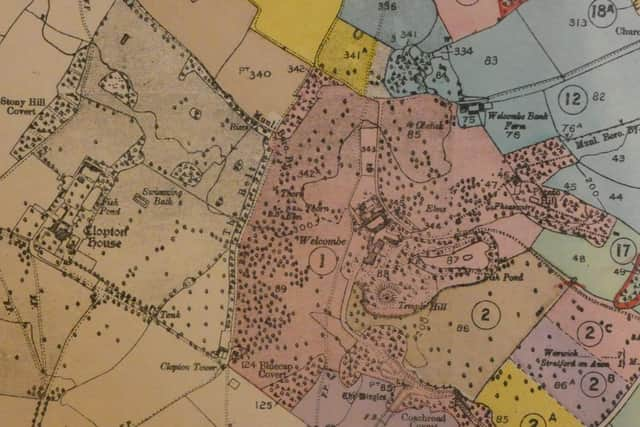

Forgotten Local Histories: The last residents of Welcombe House in south Warwickshire

Caroline Trevelyan

In 1890, the Welcombe Hills estate came into the possession of Caroline Trevelyan (nee Philips) who, compared to the rest of her family, is an overlooked figure.Her son, historian George Macaulay Trevelyan, remembered Caroline as a ‘quiet character’ who possessed a wisdom ‘that seldom speaks’ but was ‘deeply felt by all who knew her’.She was widely read in modern literature, but her ‘fullest self-expression was in the admirable watercolour landscapes which she painted wherever she went’.

Love and marriage

In 1865, the clever, pretty and politically interested Caroline first met the confident, charming and funny George Otto Trevelyan (with his square brow and thick, dark beard that was pierced only by his straight-line mouth), an aspiring MP campaigning for his first seat in Parliament.The couple fell in love instantly and were speedily engaged. Alas, obstacles to marriage no less speedily arose in the form of Caroline’s uncle, Mark Philips.The merchant wanted his niece to marry a Lord rather than George Otto, and his family’s dependence on his wealth meant that Philips’ word was final, to the immense distress of both Caroline and George.Nevertheless, in July 1869, Mark Philips relented. The persistence of the two lovers’ attraction to each other had worn down his opposition and he consented to the wedding, which took place three months later.The initial attraction was an enduring one. Such was their devotion to each other that George Macaulay wondered how one could ever survive without the other.In the end, ‘that impossible experiment only lasted from her death in January to his in August 1928’.The marriage had lasted just under 59 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFamilyGeorge and Caroline’s deeply-felt love extended to their grandchildren, whom they adored.Janet Trevelyan (the couple’s daughter-in-law) reveals that George read stories to the children and took them for rides around Stratford in the ‘beloved big carriage’, whilst Caroline kept the nursery well stocked with ‘new books and toys’.Furthermore, the Trevelyans sought to disguise some of the less endearing moments when reporting back to parents on the behaviour of their children.On one occasion at Welcombe, in 1910, a couple of the grandchildren were ‘rather exceedingly naughty’. The victims of a particularly ‘horrid cold’, they kept ‘the nursery in an uproar with their tantrums’.Caroline, however, ‘managed to conceal this very skilfully in her writing’ to the children’s parents by using somewhat selective language such as ‘I have seen no tempers’ or ‘they have been very good downstairs’.

A privileged worldOn the surface, this is a relatable anecdote with which many of us can empathise: the enduring love of a guardian when confronted with an exasperated child suffering the effects of a nasty affliction.However, George and Caroline did not have to handle the fallout from their poorly grandchildren alone as the family could afford to employ nannies and governesses who took the children upstairs when they became too much of a handful.It would be wrong to say that the Trevelyans did not spend time with their grandchildren but the level of childcare assistance they had access to is indicative of the privileged world in which they lived (by both contemporary and modern standards).The family’s privilege is also evident in the career opportunities afforded to George Otto Trevelyan.In 1862, he was invited to accompany his father, then Finance Minister for India, to the sub-continent as his private secretary. This was an appointment rooted in nepotism and granted in part as a consolation for George Otto’s failure to secure a fellowship at Trinity College, Cambridge.Later, when standing for Parliament, it was alleged that a relative bought an estate whose tenants voted with their landlord in order to secure enough votes for George Otto to win a seat in the House of Commons.The irony of this is that George Otto went on to spend a significant portion of his career campaigning for electoral reform (including extending the franchise to women) when he had essentially bought his seat and not earnt it on merit.

A successful politician?Despite serving in several government posts, including as Secretary of State for Scotland, both contemporaries and posterity have surmised that Trevelyan was not a successful politician.In the words of Humphrey Trevelyan (a distant cousin), George Otto ‘was not prepared to submit to the compromises necessary’ for success in politics and ‘he gave up rather too easily’.However, George Otto was a politician who followed his conscience by resigning from government, several times, when it pursued policies that did not align with his beliefs (such as his resignation over the question of Irish Home Rule in 1886).To paraphrase biographer Patrick Jackson: whilst George Otto’s resignations limited the extent of his political career, his ‘disinterested actions’ and ‘consistent integrity’ are ‘perhaps his main claim to be remembered’, rather than excessive ‘ambition’ or ‘self-interest’.

Author’s Note:I am deeply grateful to Norman Stevens for his comments, as historian, teacher and friend, on draft versions of the final two articles in this series. Any and all errors in these are my own.

Next Week’s Article: A Special Relationship: Theodore Roosevelt and George Otto Trevelyan