Former Advertiser reporter remembers his fresh-faced Rugby colleague whose life was cut short by tragic crash

John Shepherd brightened up many a day as he did the rounds of the Advertiser building in Albert Street.

Fresh faced, with a ready smile and pleasing charm, John was the office boy, a breed that is now more or less extinct.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYears ago, many a lad started his working life as an office boy, a sort of cross between an apprentice jack of all trades and general dogsbody.

But tragically, John was not destined to progress any further with his career.

For one Saturday night in 1967, the car in which he was travelling crossed the central reservation on the A45 Coventry road opposite the Rootes factory, and hit a lorry.

John was killed outright, along with the driver and another passenger in the vehicle. He was aged just 20.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRugby was plunged into deep shock with the news, for all three lads were well known and popular in the town.

That following Monday, I was sent by chief reporter Len Archer to speak to John’s father with a view to getting a tribute for the inevitable story that would occupy many column inches that coming Friday.

Despite the passing of more than half a century, I can still recall the father’s composure on that dreadful morning. It must have been the effects of the shock, but his words had great eloquence, and were given quite some prominence in that week’s Advertiser.

There was an even greater allocation of space given over to the reports of the funerals. In those days, reporters on weekly newspapers not only covered send-offs, but also took down the names of everyone attending.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the case of John Shepherd and his tragic friends, the funeral services were packed.

And that meant quite a lot of work for the several reporters assigned to cover all the entrances to the church, a strategy that ensured no one could slip the editorial net.

Taking names at funerals, then a standard practice across the provincial Press, was not as easy as it might sound, because there was a distinct pecking order, which went along these lines.

At the top of the list were the family mourners, followed by representatives and then last, but not least, came ‘others present’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo get these names required the patience of Job on the part of the reporter. And every name had to be spelled correctly and accorded the right status… or else.

If you think that’s easy, consider this. Some mourners spoke indistinctly or had heavily accented voices. Others might have speech impediments such as a stutter.

Then there were the individuals who loftily refused to co-operate with a lowly member of the Press, had bad breath, or perhaps there would be a combination of both.

These types were often the first to complain to the Editor when their name failed to be in the correct section in that week’s edition of the paper.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn my book Beef Cubes and Burdock: Memories of a 1950s Country Childhood, I describe covering the funeral of Lord Cromwell of Misterton Hall, near Lutterworth.

The Advertiser reporters certainly went along mob-handed to this job, with no fewer than four journalists, including the chief reporter, assigned to cover the story.

As we sped along the Leicester Road in the office van, Len Archer briefed his troops.

The basic plan was to station two reporters at the front and back of Misterton Church, to ensure every name was taken down.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI was the youngest in this gang of four, and Len wanted to satisfy himself that I had been listening to his campaign strategy, and therefore thoroughly understood.

“Now boy,” he said, “If you see a group building up at the lychgate, whatever you do, don’t move into ‘em. If you do that, they’ll get round you. Wait for them to come to you, boy.”

Len planned everything with a military precision, like the efficient general he undoubtedly was.

Well, being a stupid-boy-Pike character to his Captain Mainwaring, his instructions went in one ear and out the other. And when the time came and, as predicted, mourners started to gather at the lychgate, I did exactly what I shouldn’t have done.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI started advancing down the church path, notebook and sharpened pencil in my hands, like some kind of editorial infantry soldier marching to meet the foe.

And to complete this martial scene, I had not gone more than a few yards when Len’s booming voice rang in my ears… “Fall back, boy, fall back!”

Which is what I did, retreating backwards at a fast rate of knots. Meanwhile, the mourners looked on in astonishment as I was given a dressing-down, with Len oblivious to a sea of shocked faces.

So there you are – a lighter moment in what for many would represent nothing but sadness and personal grief.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe days of local reporters dutifully taking down lists of names at funerals are long gone.

And while the role of the office boy has also vanished into the mists of time, there will still be Rugby people who remember young John Shepherd and his tragic mates, taken from their families and work colleagues long, long before their time.

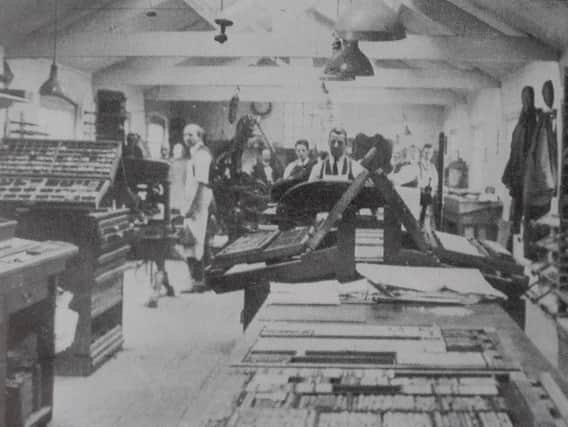

John Phillpott’s latest book, Go and Make the Tea, Boy! an account of his days on the Advertiser, is published by Brewin Books of Redditch.