Former Advertiser reporter remembers the Churchover man killed in the Somme more than a century ago

A chill wind sweeps in from the north-east, spotted with rain drops that seem to search for and find any exposed part of the body, seemingly mocking the fact that you’re buttoned up against the cold.

Large, hedge-less fields roll away in one direction, undulating expanses of green and brown, streaked with slashes of white chalk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTurning your gaze, and all you see are not so much woods, but a broken spread of spinneys, their leafless fingers of branches grabbing at the pale blue autumn sky.

This could so easily be northern Warwickshire where it meets Leicestershire. Except it isn’t.

For this is the Somme, northern France… the blood-soaked Somme of dark legend.

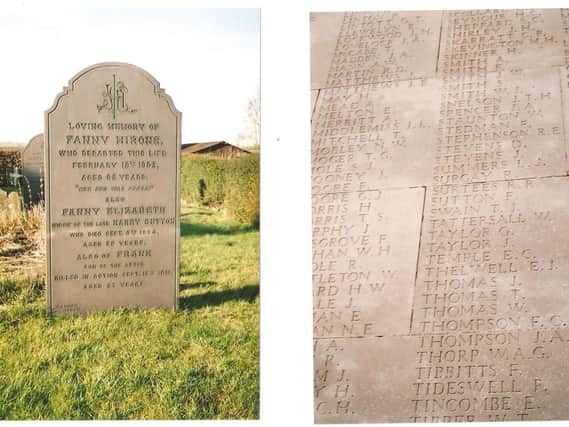

I’m standing at the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme and I’ve just found a name. It’s just one of more than 72,000 inscribed here, but it has a certain resonance as far as I’m concerned.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor the name is that of Frank Sutton, Grenadier Guardsman, killed in September, 1916, on the most notorious battlefield in British history.

But what it doesn’t record, of course, is that Frank Sutton was a son of Churchover, near Rugby.

Frank and I share a bit of history, as it happens, despite the fact that he died 33 years before I was born. He was brought up in School Street, Churchover, just as I was, went to the local school like me, and no doubt fished and swam in the River Swift, just as I would do a few decades later.

I’ve been to the Somme many times. But it was Frank’s name that caught my imagination, because a few weeks before my trip to France, I had found his parents’ grave in Holy Trinity churchyard, Churchover.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was a reference to him on the gravestone, recording how he had been killed in action in France during 1916. And it was this information that spurred me to not only research his brief life, but also to visit the area where he was killed.

Frank was a gardener by trade, and from that I deduce that he either worked at the Old Rectory just down the street from his home, or at nearby Coton House, a stately pile that would have employed many men to work its extensive grounds.

No doubt he responded to Lord Kitchener’s call for volunteers when the First World War broke out, and it would be this that sealed his fate.

Perhaps his first choice might have been his county regiment, the Royal Warwickshire. We have no way of knowing. In any event, he was enlisted into the premier regiment of the British Army, the Grenadier Guards.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to my reference books, the Guards battalions were heavily engaged with the Germans in September of 1916, and Frank was killed.

His body was never found or identified.

In my book Beef Cubes and Burdock: Memories of a 1950s Country Childhood, there is a chapter in which I imagine the circumstances of Frank’s last moments of life, titled When Johnny Came Marching Home.

During one of my visits to Thiepval, I picked up an acorn while walking through woodland. I put it in my coat pocket, and upon my return to England, planted it in a pot at my home.

The following spring, a small shoot emerged, which then became a sapling.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd then a thought occurred. If I were to gain permission from the relevant authorities, perhaps I could plant the tree in Holy Trinity churchyard, therefore representing the symbolic return of a son of Churchover after nearly a century of absence.

Well, after various letters and many phone calls, I eventually got the go-ahead.

And on a freezing cold March day, following a service at Holy Trinity, I planted that little Somme sapling not far from the grave of Frank’s parents, the ceremony witnessed by several villagers.

And that would have been the relatively happy ending to just one tragic tale of the First World War, except for one thing. Despite the fact that the sapling grew into a small tree, I was deeply saddened when, on a subsequent visit to Churchover, I discovered that it had died.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPerhaps it perished from natural causes. After all, plants do die from time to time, with no apparent cause. Or maybe someone, somewhere, knows something.

However, I very much doubt that I will ever know the reason.

Nevertheless, during this Remembrance Season, my thoughts will once again turn to Frank Sutton, that brave son of leafy Warwickshire who left home and hearth for the Somme, never to return… except in spirit.

So. I will now close with the immortal words of Rugby poet Rupert Brooke, a most fitting epitaph for Frank Sutton, I think you’ll agree.

If I should die, think only this of me;

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England

John Phillpott’s third book Go and Make the Tea, Boy! was published this summer by Brewin Books of Redditch.