Former Advertiser reporter remembers the famous son of Warwickshire whose genius helped to destroy tyranny

Whenever I think of the wartime men and women who guaranteed my generation’s freedom, it’s not just the soldiers, sailors or airmen who spring to mind.

For while bravery on the world’s battlefields and home front must always be remembered, we should also never forget the backroom boffins who helped to make ultimate victory possible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the most famous was, of course, R J Mitchell, the man who – though stricken with terminal cancer – worked day and night to produce the Spitfire, that celebrated fighter of the Second World War.

But while the wonderful and deadly grace of that iconic plane will always have a place in British hearts, it should also be remembered that we have just as great a hero in our own neck of the woods.

That man was Frank Whittle, inventor of the jet engine. And although born just 12 miles away in Coventry, he was destined to have many links with Rugby and Lutterworth throughout his eventful life.

Frank Whittle was born on June 1, 1907 in Earlsdon, the son of a Sara and Moses Whittle, a mechanic. His first attempts to join the RAF failed as a result of his lack of height, but on his third attempt, he was accepted as an apprentice in 1923. He qualified as a pilot officer in 1928.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a cadet, Whittle had written a thesis arguing that planes would need to fly at high altitudes, where air resistance is much lower, in order to achieve long ranges and high speeds.

Piston engines and propellers were unsuitable for this purpose, so he concluded that rocket propulsion or gas turbines driving propellers would be required. Jet propulsion was not in his thinking at this stage.

By October, 1929, Whittle had considered using a fan enclosed in the fuselage to generate a fast flow of air to propel a plane at high altitude. A piston engine would use too much fuel, so he thought of using a gas turbine. After the Air Ministry turned him down, he patented the idea himself.

As a pilot officer, he moved to the Central Flying School in 1929 to qualify as a flying instructor. In 1935, Whittle secured financial backing and, with Royal Air Force approval, Power Jets Ltd was formed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey began constructing a test engine in July, 1936, but it proved inconclusive.

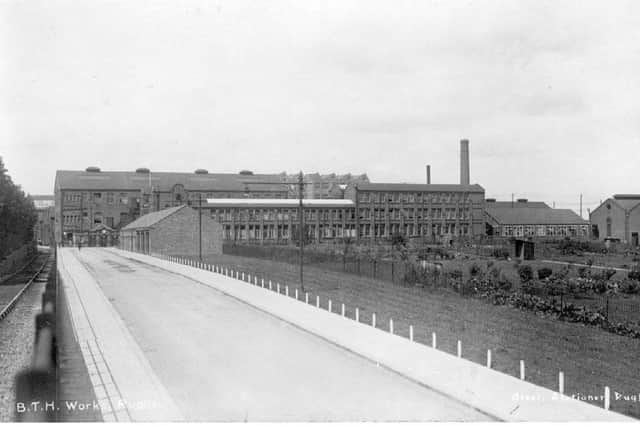

Placed on special duties, Whittle had been allowed to supervise the manufacture of components and the building of his engine, which he ran successfully at the British Thompson-Houston works at Rugby on April 12, 1937.

However, Whittle concluded that a complete rebuild was required, but lacked the necessary finances. Protracted negotiations with the Air Ministry followed and the project was secured in 1940.

By April, 1941, the engine was ready for tests. The first successful flight by a Gloster-Whittle jet aeroplane took place on May 15, 1941, from Cranwell in Lincolnshire.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir Frank telegraphed his team of engineers at their offices in Brownsover Hall, Rugby, to tell them of its success. The team opened a precious bottle of champagne to celebrate, and each of them signed the label on the bottle.

By October, the United States had heard of the project, and asked for the details and an engine. A Power Jets team and the engine were flown to Washington to enable General Electric to examine it and begin construction.

The Americans worked quickly and their XP-59A Airacomet was airborne in October 1942, some time before the British Meteor, which became operational in 1944.

Soon, the Meteor was blasting enemy doodlebugs out of the skies. And although the Germans had also developed a jet fighter, it had come about too late to make much difference to the air war in which the Allies were gaining complete superiority.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhittle retired from the RAF in 1948 with the rank of air commodore.

He was knighted in the same year and went to work in the US shortly afterwards, becoming a research professor at the US Naval Academy at Annapolis. Whittle died on August 9, 1996.

Lutterworth and District Museum has a unique archive of memorabilia of Sir Frank Whittle, Power Jets, and the early history of the jet engine. The museum holds the original patent for the concept of the jet engine, registered by Sir Frank in 1930, and also that famous champagne bottle.

During the war, Power Jet’s office building was at the Ladywood Works in Lutterworth. The first floor window, from which Sir Frank shot rabbits to supplement wartime food rations, still stands.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMuch of Power Jets’ work was subsequently transferred to Whetstone, near Coventry. Whittle was awarded a CBE in the 1944 New Year Honours and six days later, bowing to US pressure, the jet engine was made public, making Whittle a national hero.

Leamington Spa also has links with the inventor of the jet engine. When I worked in the town during the 1970s, I used to frequent a pub called ‘The

Jet and Whittle’, a hostelry that was proud to be named after a great son of Warwickshire whose genius helped defeat the forces of tyranny.

John Phillpott’s book Go and Make the Tea, Boy! an account of his early days on the Rugby Advertiser, is available from booksellers and the internet.