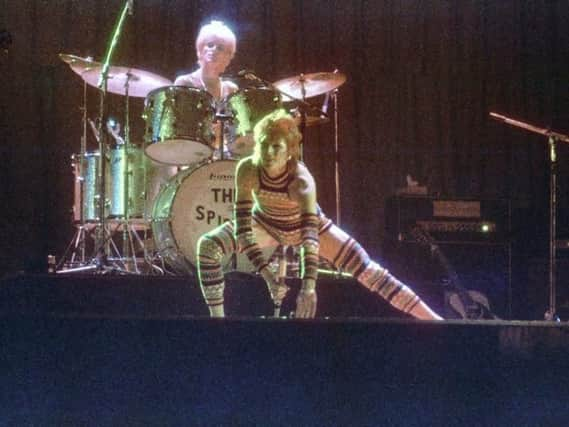

The last Spider from Mars: Woody Woodmansey on life and work with Bowie ahead of Leamington gig

It's Friday January 8, 2016. Woody Woodmansey is in New York and it's David Bowie's birthday. Woody is drumming with Holy Holy, the band he's formed with Bowie's long-time producer Tony Visconti. During the show, Visconti calls Bowie. The crowd sing him Happy Birthday; Bowie thanks them and asks for their verdict on Blackstar, the album he's released that day. Their response is rapturous. Bowie wishes the band good luck and says he'll catch them later on the tour. Within two days, Bowie has died.

"That was pretty surreal," says Woody now. "And we had to decide how we'd continue - out of respect, do we pull off the road? But Tony had said 'look, he worked right to the end - he didn't give up'. And I said it was the same even on the early Ziggy tours - he wasn't always eating properly, and he'd get flu, and we'd go 'we can't play tonight - you can hardly talk', and he'd go 'no, if you're booked, you always turn up. If you say you're going to play, you play'. So we said, OK, let's follow his motto on that. So we carried on."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd carry on they have done, playing to sell-out crowds and receiving widespread acclaim. Their new tour starts next month and stops off at the Assembly in Leamington on Saturday February 23. It's a chance to hear songs from arguably Bowie's most significant era played by musicians who were there at the time.

"It was very hard to go out there and play the songs that bring back the memories even stronger when you know he's gone," says Woody of playing in the aftermath of Bowie's death. "And you've got the first 12 rows with their hankies and tissues out and you're thinking 'oh God, what have we done?'. And I ended up every night saying look, this is not an effing funeral, it's a celebration of his music and his life. So he would want you to have a good time. That seemed to work every night."

To his great credit, Woody does not sound like a haughty, hoary old rocker living in the past. He is affable and earthy, with a ripe Hull accent and a ready laugh. This, from a man who played on the albums The Man Who Sold The World, Hunky Dory, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, and Aladdin Sane. He's there on Changes. He's there on Life on Mars?. He's there on Starman and Suffragette City. He's there on The Jean Genie. That's him playing one of the great openings to a rock album: the mournful yet driving beat that slowly emerges from the darkness into Five Years, a beat Woody crafted and which is so resonant and evocative that Bowie deployed it again on his 2013 comeback album The Next Day. Bowie's success was built on those songs; and those songs are built on Woody's foundations. Musicians with half his legacy often seem to have twice his ego. It's almost as if what he's accomplished hasn't quite sunk in. Has it?

There's a pause. "No, probably not. I don't think any artist that does something like that really grasps the full effect. I still get emails and letters and all sorts that are just, oh my God. There were two brothers who were drafted to Vietnam and they said 'we just want to let you know we took Ziggy with us. That's the only cassette we had. And if we hadn't have had that with us, we wouldn't have come back'. And you go - gulp. And there's lots of stories like that, and they still come in. It's not something you're thinking about when you're on the road or in the studio. You just hope that it does help or that it does communicate something that someone enjoys listening to and it helps in some way. I don't even think David grasped it, to be honest."

************

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWoody - real name Mick - found his vocation as a teenager. Influenced by the hard-hitting, hard-living likes of Mitch Mitchell, Ginger Baker, Keith Moon and John Bonham, he got into the local heavy rock scene and joined a band called The Rats, led by a guitarist named Mick Ronson. Bowie, then little more than a one-hit wonder with Space Oddity his only success, hired Ronson in 1969. On his recommendation, Woody followed. But on their first meeting, it was as if Woody was auditioning Bowie, rather than vice-versa.

"I had no clue who he was," says Woody. "I'd seen a flyer for an open-air festival and it had a picture of him with curly hair. And I knew he'd done a single about space that fitted with the moon flight. That was as much as I knew. And he was a folk guitarist. I still hadn't got my head round what Mick Ronson, who was probably one of the loudest lead guitarists, was doing with a folk guitarist.

"And I guess I had a checklist in my head - is he thick? Does he know what he's talking about? Can he write? Can he sing? Does he look good? Does he look like a good frontman? Is he nervous? So I sat for a few hours in his lounge with him. And he played me some of the early early albums, and they were very folky and I thought 'I haven't heard the drums yet'. And it didn't really float my boat. Then he picked up his 12-string and played Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud. That just had me.

"By the end, I'd ticked 'well he can sing, he can write, so there's potential here, he looks cool, he knows what he's talking about', and I thought 'OK, I think I've made a right move here'. But I had to get those boxes ticked. I was used to Roger Daltrey, Paul Rodgers, Robert Plant, those kind of singers. And he definitely didn't sound like them. But I thought he was very British, and had an amazing ability to put things across."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo Woody agreed to take him on. Together, they recorded The Man Who Sold The World. But it was not until they made Hunky Dory in 1971 that the full extent of Bowie's talent became evident, the key moment for Woody being the recording of Life on Mars?.

"Ken Scott, the producer, said 'come in and listen'. So the four of us went in. When you listen in a mixing suite, the quality is out of the roof. And so our mouths were open. And at the end I went 'is that us?'. It just sounded so incredible. And it made you think, hell, there's more arrows to this guy's bow than he's been using up to now."

Yet the goings-on in the studio were only a part of it. From those early days, vision was as important to Bowie as sound - with startling consequences.

"Then the mime things came out," says Woody. "He played a video of him doing mime on the first day we met. I thought 'what has this got to do with rock'n'roll? I'm glad I wasn't around for that'.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"But then the mime things came out on stage. And you went hell, this is different - he's going places where nobody has gone before. And then you wouldn't have had your Madonnas and your Lady Gagas and your Prince. When we talked, he said 'let's brighten the music business up. It needs some colour, it's drab. It needs to be controversial, it needs to be dangerous and edgy. Are you willing to play the game and do that?' And we said 'yes - there's a limit, but yes'."

The result was a rocket-ride to stardom. "It was kind of beyond your wildest dreams, really," says Woody. "At 15, when I started, you have your own imagination of what it's like being in a top rock band. You've watched The Who or The Small Faces or The Kinks walk on stage and you think 'where did they come from? Where do they go after the show? Where did they get those clothes?'. And you don't have any idea.

"And then, when you're in it, you know all those things. And it's wilder than you thought. Anything the world has at that time is on offer. So you have to be pretty selective!"

As for what would surprise people most about Bowie at that time, Woody is clear.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"He had a very down-to-earth sense of humour. In the early days you wouldn't think he had a sense of humour. When he'd answer some questions, they were very oblique, off-the-wall answers that just added to the sense that he's weird. Not that you'd say 'I see Leeds Utd won', or 'Ziggy, do you have any change for the taxi?'. Because he definitely didn't have! But he was very normal."

But life in Haddon Hall, the sprawling Victorian villa in south London where Woody lived with Bowie, Bowie's wife Angie and assorted hangers-on and passers-by, was hardly conventional - and nor was Bowie's behaviour, aspects of which seem to baffle Woody to this day.

"There would be different nationalities - Australian or Canadian or whatever," he says, giving one example. "And in two or three minutes he was talking with a complete Australian accent. And we would be listening, and I would think he's going to get a thump in the mouth - he's taking the mickey out of this guy. But he never did get that. He was genuinely just being an Australian. It was quite weird. He did it seamlessly. And then another accent - if it was an East End London boy, he would be talking like that. He'd give it back as if they were talking to themselves."

The rise of Ziggy and the Spiders had been spectacular indeed. But so was the fall. On July 3, 1973. the band played at the Hammersmith Odeon. Bowie's words that night to the audience, just before playing the night's final song, Rock'n'Roll Suicide, were dramatic indeed: "Not only is this the last show of the tour, but it's the last show we'll ever do." As an act of artistic daring, it was remarkable: Bowie appeared to be killing off his career at its peak. Of course, it came as an immense shock to the fans. But what was even more extraordinary was that it came as a surprise to many in the band - including Woody. At the end of the show, he threw a drumstick in Bowie's direction - although with no intention of hitting him - and followed Bowie to the after-show party. But there was no way to get to him, surrounded as he was by the likes of Mick Jagger, Lou Reed and Ringo Starr. Woody would have to wait to confront David about his fate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFour days later, Woody received a call from Bowie's manager, Tony Defries; he told Woody that he was sacked. Bad enough, one might think; but the call came on Woody's wedding day. Bowie had retained the services of Ronson and bassist Trevor Bolder for the forthcoming album Pin Ups; Woody had been dispensed with. Bowie refused to speak to him. But the wounds were healed when the pair met in 1976, and it is impossible to discern in Woody's voice anything but the sincerest affection for his former singer.

************

There had long been a curious absence from Bowie's career: he had never toured The Man Who Sold The World, an album of dark, strange, enigmatic and at times heavy music, seemingly tailored for live performance. So when Woody and Visconti formed Holy Holy with the express intention to do just that, Bowie gladly gave them his blessing. They began touring in 2014 and have had an array of contributors, including Marc Almond, Clem Burke of Blondie and Gary Kemp of Spandau Ballet. They will be joined on their forthcoming tour by Glenn Gregory, the frontman of Heaven 17. There is no shortage of Bowie tribute acts on the circuit at the moment - but Woody insists Holy Holy are something quite different.

"With David, he'd say 'if we go out on the road, it's not like a studio, doing an album. So I don't care if you mess up - if you're playing in the right spirit for the song, that's what it's all about'. So we kind of put that in with Holy Holy. Not that we play bum notes - but there's 500 different artists and bands that have played or can play those songs. Any decent musician can play them. But do they know how to play it, to put it across right? So we're more into that.

"I've found that fans are not stupid. They really do know if you mean it. They know if you're playing by numbers. And we definitely mean it."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn addition to The Man Who Sold The World, the crowd is promised an array of other songs from 1969 to 1973 - many of which have always sounded better live than on record, to fans and to Woody: "The funny thing was we did some of Hunky Dory and Ziggy on the BBC sessions. And I always liked them better, because it was raw, you did one take, and it just had something else, that real essence of good players getting it on."

The fact the music has endured to the extent it has - with Bowie recently voted the greatest 'entertainment icon' of the 20th century in a BBC poll - now comes as no surprise to Woody. But how would he have responded in the early days if someone had told him the songs would still be loved by millions nearly 50 years later?

"I would have said 'get real! If we're lucky, it might last a couple of years'. Which most music does. It's a total surprise that it's still played weekly on the radio. It just shows the talent.

"I thought one of his genius aspects was when he wrote a song, his ability to use words that gave you pictures and gave you somewhere to go and make the story up, rather than him telling you everything about it. He just had that ability to get across often very surreal viewpoints that grabbed you, which is a real art. I think he kept that up all the way through. I always thought he could write a single that would be a hit any time he wanted. But he didn't always want to do that."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWoody takes the longest pause of our conversation as it reaches its end. He is contemplating how he would like his work with Bowie to be remembered. It surely says something significant that it appears he's never thought about this before.

"Good question," he says. I wait and wait and fear the line has gone dead. Then he says it.

"Rock and roll music that ticked all the boxes."

Just like Bowie did for him. And just like he did for Bowie's years of stardust.

* Holy Holy play the Assembly in Leamington on Saturday February 23. Visit leamingtonassembly.com to book.