How Kenilworth experienced one of its darkest chapters when many died during World War II air raids - 80 years ago this month

and live on Freeview channel 276

Eighty years ago, Kenilworth experienced a dark chapter in its history when many civilians died during November 1940. Here is an updated article by local historian Robin Leach, which we first published ten years ago to mark the 70th anniversary.

Each year, as Remembrance Day passes, thoughts inevitably turn to November 21, 1940, the date of the most significant incident in Kenilworth in living memory; an event that had repercussions for decades.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCoventry started to suffer sporadic air raids from July 1940 and they continued as winter loomed.

With aircraft mostly approaching from the south, Kenilworth’s anti-aircraft positions at Rouncil Lane was in regular use. On Thursday November 7, shrapnel from one of these fell to ground at 7 Arthur Street just as Sarah Collett opened her front door. Sarah was the first person to die in Kenilworth in the conflict.

At 7pm on November 14, the most devastating raid on Coventry started. Over 500 aircraft in several waves flew over Kenilworth towards their target. The anti-aircraft guns were again in action and Gladys Lawrence, 27, at 14 Hyde Road became the second to die in Kenilworth, from a ‘stick’ of bombs that fell in a line from the Working Men’s Club to Manor Road.

A ‘stick’ of five bombs also landed in a line at Watling Road (where a house was slightly damaged), the railway embankment near the gasworks, and three on the common; one left a large crater but it is thought the other two buried themselves deep into the soft terrain and may still be there today.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStray bombs are known to have fallen at Manor Road and Villiers Hill, and another in the fields across the road from Red Lane with shrapnel damaging nearby houses. Although the dates of these incidents appear to be uncertain, it is probable that some at least were on the night of the Coventry Blitz.

As so much of the City of Coventry was destroyed, many people were homeless and others simply sought out a safer refuge; over the following week hundreds made their way to Kenilworth. On Wednesday November 20, the day of the first mass burial of Coventry blitz victims, no fewer than 70 Coventrians gathered at ‘The Globe Hotel’ at Abbey End awaiting dispersal to anyone who would take them in, and during that afternoon they were all found somewhere to stay. The Globe was particularly accommodating as the landlord James Stanley was from Coventry; amongst his guests was his son Ralph, on leave from the RAF for the birth of his first child.

With two civilian deaths in the previous fortnight, bombs falling around the town, a flood of evacuees arriving and its emergency services routinely assisting in Coventry during air-raids, Kenilworth was suddenly on ‘the front line’.

Abbey End was originally very narrow but was widened in the 1930s. Partly residential including several new houses, it also had Oscar Lancelotte’s Tea Room and Confectionary, a doctor’s surgery and the drapery of Smith & Millar. At its southern extremity, Abbey End opened out into The Square; The Globe Hotel, with the address of 3 The Square, was in line with the Abbey End buildings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the night of the 20th, there was a major raid on Birmingham. At 2.30 am, the drone of a solitary aircraft heading northeast towards Coventry was heard. Suddenly, there was a massive explosion; a landmine had fallen in a field at the point where today Oaks Road and Beauchamp Road meet. The nearest houses in Chestnut Avenue had windows blown out, as did some in St Nicholas Avenue, otherwise there was little damage but a very large crater.

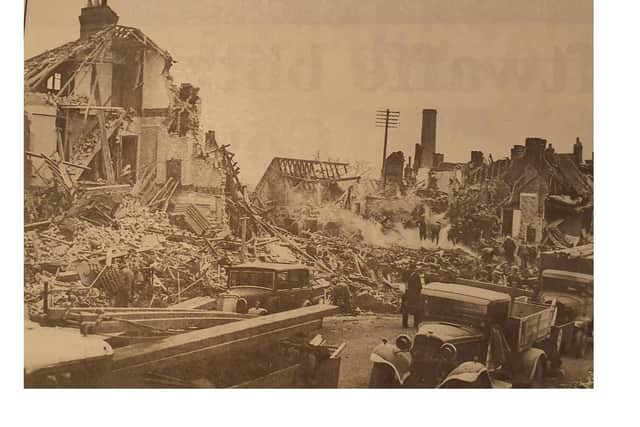

Within seconds, there was another immense, shattering explosion; a second landmine on a parachute had detonated in the town. The centre of the blast was at 3 and 5 Abbey End, Smith & Millar the drapers. Guests for the night, Mr and Mrs Glennie, Mr and Mrs Snape and their nephew, all from Coventry, and residents George and Nellie Webb died; proprietress and host Isabella Smith was badly injured and died a week later.

Either side, buildings were also totally destroyed; at number 1, confectioner Oscar Lancelotte lost his wife Winifred, and guests Mr and Mrs Lucas and Mr and Mrs Allen, all from Coventry, died. At number 7, Mr and Mrs Saunderson from Coventry died, but their host survived. A few walls remained of number 9 where Grace Halls of Coventry died.

Across the way, number 2 Abbey End was gone, killing Tom Bristow of Lincoln and 31-year-old local girl Annie Lee; at number 6 resident Lavinia Redwood died.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome of The Globe had been blown away, but much survived protecting those within. Perhaps as many as 50 had stayed the night at the inn, all but three survived; Bertie Lamb and widow Rose Lane, from Coventry, and Ralph Stanley, son of landlord James, died – his son was born just hours later. Directly opposite, 1 The Square was severely damaged, killing residents Beatrice Astle and her daughter Louie.

Rescue teams descended on the area. Kenilworth’s firemen, still weary having just returned from Coventry an hour or two before, were joined by other fire crews, Civil Defence and Home Guard units and volunteers who worked together throughout the night and much of the following day.

70 civilians with injuries were taken to the medical centre set up early in the war at St John’s church hall; the town’s ambulance was kept in a garage erected in the car park there and was used to take the more severely injured to hospitals throughout mid-Warwickshire.

Kenilworth’s cemetery chapel became a makeshift mortuary; the pews were removed and as victims were recovered, they were laid on the floor on covered sheets of corrugated iron. 25 died in the explosion, one of whom were never identified.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe attack was known about in the country of its origin: the traitor Lord Haw-Haw is reputed to have stated on air that the devices were not intended for “the little hamlet of Kenilworth”.

The devastated area was quickly cleared and left for the weeds to grow. The damaged buildings on the periphery that were not demolished carried ‘temporary’ repairs, some until the 1960s.